BUFFALO, N.Y. — Asking sports fans about their favorite memories always brings a flood of emotion. The in-game moment is always the central focus, but there are those ancillary details that are critically tied to what happened.

It’s often combined with the visual of reactions for players and fans, benches and spectators. There’s the audio sound of the crowd’s roar — or the lack thereof — adding to the positive euphoria or negative shock. And there’s the broadcaster’s call, the analysis that forever attempts to explain the moment.

The moments are organic, but they’re captured through the creativity and innovation of the network tasked with their delivery. It’s a massive undertaking, and it’s one that, for 15 consecutive seasons of the Frozen Four has rested on the shoulders of a dedicated and talented ESPN crew.

“The technology that ESPN brought this year is really cool,” analyst Colby Cohen said. “ESPN brought [dozens] of technologies, with so many different statistics and graphic element opportunities that we will use. Some might not be as apparent to the viewer, but there’s multiple trucks with crews that are incredible to see. Buffalo and the Sabres were great with giving us all the space we need, and the Pegula family is one of the reasons why we can do what we want to do. When I got here, I saw the capabilities, and I’d never seen some of it before. It’s just great to see the network step up to the plate.”

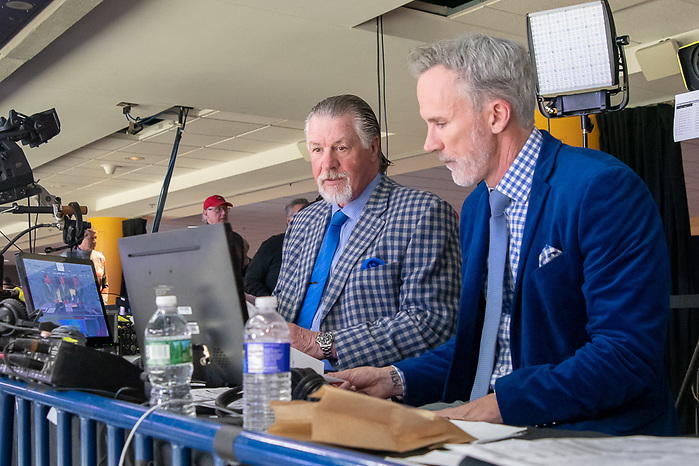

Cohen knows a little something about broadcast additions; he’s one of them this year. The former Boston University national champion joined the ESPN roster this year as an on-ice, between-the-benches analyst, an augmentation of sorts to the regular broadcast team of John Buccigross and Barry Melrose. It was one piece of a puzzle that included an on-site studio for intermissions and both pregame and postgame shows, along with the technological advances that helped bring the product to viewers watching at home.

Technically speaking

An ESPN production is widely recognized as the finished product, but it’s really the finished sum of a number of smaller productions behind the scenes. The network employed a team of more than 50 employees on site in multiple production trucks, all producing different elements of a broadcast that began at KeyBank Center at the beginning of the week and stretched back to meetings well before any team earned its spot in Buffalo.

“We were at the NCAA regionals two weeks ago, and the most-resourced one only had six cameras,” senior coordinating producer John Vassallo said. “Here in Buffalo, we have 16 cameras. It’s an equipment complement similar to professional championships. There’s a group of really talented people that is, in its own right, terrific, [but] we don’t do a bunch of college hockey throughout the year. So we have to be able to hit on all cylinders from period one of the first semifinal. We have to know what he know how to do — cover the game as intimately as possible — while utilizing the resources for a crew and team that isn’t on its fourth round of [postseason coverage].”

That meant the on-site work began at the beginning of the week. The first operations group arrived on Sunday and began work on Monday when ESPN’s trucks first rolled into the KeyBank Center. It continued through Tuesday and into Wednesday, ultimately culminating after 2½ days of technical setup.

That infrastructure included audio and video elements capable of capturing anything anywhere on the ice. ESPN installed around 25 cameras and approximately 30 microphones around the arena to capture viewpoints not usually seen in the college game, and those, in turn, dictated how the production staff in the truck could establish a general operational approach for a live broadcast. It was a huge enhancement from the NCAA regionals coverage two weeks ago, when ESPN utilized substantially less visual components, for a network that admittedly doesn’t broadcast much college hockey during the regular season.

“The tape, the support, the statistics people dialed in on Wednesday night,” Vassallo said. “We had a production meeting for two hours the night before the semifinal to establish a two-pronged approach. It’s about making sure the technical end and operational end are both prepared, and when they mesh, they make really great television. That’s not unlike what we do with the NBA. It’s the mantra of sports production.”

That combination produced a long day of hockey coverage that needed to transcend the actual games while keeping the focus on the ice. In the truck, the audio and video crew translated their own raw information into fully-dimensional game presentation by combining different elements. It’s a fully dynamic situation where the staffers try to focus on themselves while keeping a general awareness on others.

“We want people to produce their area,” Vassallo said. “Peter Jensen, for example, is doing graphics, so we want him to have graphics that are accurate, well-researched and put together. But we also wouldn’t want him to turn a blind eye to other areas. We want a lot of eyes on the screen. Everyone is doing their individual job, but they have to look out for the person to their left and right. You produce your own area but have a vested interest in the whole. When everyone is doing their individual job, it becomes a pure additive situation.”

The voices of ‘Cawledge Hawkey’

Any technological advance allows for greater capability, and the most public-facing enhancement of ESPN’s 2019 Frozen Four coverage came from its most visible advocates: the broadcasters.

While Buccigross and Melrose returned to the booth for their seventh Frozen Four together with sideline reporter Quint Kessenich, the addition of Cohen was a new grand opening after the soft opening in the Northeast Regional earlier this year.

“I believe it’s a credit to ESPN to grow the game and grow this event,” Cohen said. “ESPN is great for hockey, and the more hockey that is on ESPN, the more the sport will grow. I’m not that far removed from playing in one of these, and I work in the NHL with the Philadelphia Flyers. So putting me on ice level is an opportunity to enhance the show.”

This year marks 10 years since Cohen became an immortal name at Boston University. He scored the game-winning goal in the 2009 national championship game against Miami, the last such title that the Terriers have won. Following BU, he played a handful of years professionally, including a stint as a reserve for the Boston Bruins’ Stanley Cup championship in 2011. His playing career ended in 2015, enabling him to transition to a career in both radio and television.

“Colby was someone we talked to a couple of years ago,” Vassallo said. “I’ve been impressed with him, his delivery and personality, and I thought he would be really good [for ESPN]. We threw him on for a couple of regular-season games, and we thought he did really well. So we took a flier on him [with the NCAA postseason].”

Two weeks ago, Cohen joined Buccigross and Melrose in Manchester, N.H., for the Northeast Regional. It turned into something of a soft opening for the Frozen Four coverage, a seamless transition from a two-person team into a three-person broadcast complemented by Kessenich, who remains an ESPN reporter staple to the college sports game.

“Barry was a hockey player and a successful one, but he coached Wayne Gretzky,” Cohen said. “He coached some of the best players who ever played the game. He has a unique vision and aspect in the way he sees things. A lot of it isn’t on air. It’s the stories off-air that help me realize how he looks at the game, and it lent to developing our chemistry during the regionals.

“And with [Buccigross], it’s a really unique case,” he said. “Hosts and play-by-play guys give broadcast calls, but sometimes that’s all they bring to the table. He is another analyst who really knows the game. He’s a face for college hockey. When you have a play-by-play guy who understands the game like an analyst, it makes your job easier. He drives the broadcast, with Barry and me as his left and right wings.”

It’s an area where Cohen is starting to spread his own talents and blossom into the game’s next potential star. He integrated into the ESPN broadcast in a way that made the product fuller and more complete, especially in consideration of what the truck-based teams can do by way of replay, angle, sound and graphics.

“Barry would finish a point and, without a prompt, send it to Colby to advance it,” Vassallo said. “[Producer] Anthony DeVita would then traffic Colby for an update, and he would make a point to query back to Barry. The way they integrated and meshed with different perspectives was a pleasure to hear.”

Studio central

The sheer size of production would have sufficed with the combination of Buccigross, Melrose, Kessenich and Cohen, but ESPN instead went a step further this year by incorporating an on-site studio for game downtime. It was an attempt to continue generating a big-event feel for college hockey that’s commonplace across ESPN’s college football and basketball coverage, as well as professional outlets throughout the industry.

“Having a studio on site is so cool because it’s like College GameDay [for football],” Cohen said. “Sean Ritchlin won two national championships, and Dave Starman knows more about college hockey players than anyone. That’s a talented group, and it’s a big-time feeling that it should be [for college hockey]. Every game is Game 7. People love this event.”

Producing that outward presentation, however, created even more production ingredients into an already challenging recipe. A studio toss, for example, can run on its own schedule with its own breaks, and everything, from the lighting to the sound to the timing, can remain static. A live shot involves more variables, from background lighting of the teams’ entrances to the timing of the national anthems.

“We had four intermissions [across the two games], but we had the [60-minute] break in between games,” Vassallo said. “Everything that happens between games, you can easily work around when you’re sending to a studio in Bristol, but now it needs to be built into a plan. You either want to cover a national anthem or be in break. That whole process is more manpower, more technical work for people like [producer] Rob Lemley and [director] Bob Frattaroli in production. So you just have to tell people not to sweat the small stuff. For the hockey fan, it’s going to be a win. That’s what we were after.”

It’s all part of the changing and growing nature of college hockey. The ever-growing maturity of the internet enabled new mediums, which in turn raised the technological bar for how everything, especially in sports, are presented. The challenge quickly became about fast innovation, which now drives the growth of awareness within the sport itself.

“When I was at BU, I hadn’t heard of many of these teams,” Cohen said. “There was no Twitter or Instagram, and we didn’t see teams or highlights on social media. We didn’t live in the Stone Age, but I had a Blackberry in college. We didn’t play teams like Bowling Green or [American International]. So it’s great to show the quality of players out there, how the coaches are recruiting, and how they’re developing players like how [these Frozen Four teams] have done.

“2009 comes up [for me] and I smile, but it’s off my radar a little bit,” he said. “I don’t ever want to take away from the current event. I want the game to stay about the game. I was definitely rooting for [BU] in 2015, but I’m also out there covering teams and seeing other programs that I’ve come to like. I get to meet coaches from other programs, and I’ve come to really respect and become fans of a half-dozen to a dozen other teams. I’m so impressed with what’s happening [across college hockey], with a lot of really good programs out there teaching good hockey.”