The game was more than half over and the outcome still in doubt when North Dakota senior forward Matt Frattin scored an electrifying breakaway goal to give the Fighting Sioux a 3-1 lead.

It brought the crowd of more than 11,000 to their feet, and soon the chant of “Hobey Baker!” echoed throughout Ralph Engelstad Arena. Behind Frattin’s insurance marker, the Fighting Sioux surged to defeat Bemidji State 5-1 on Feb. 27 and stake a claim to their 15th WCHA championship.

The previous weekend at St. Cloud State on a night when the frontrunners in the WCHA title race all lost, the Sioux were trailing by a goal late in the third period. Frattin split two defenders, outraced a third and beat Huskies goalie Mike Lee to salvage a tie and earn an important point for UND.

Although he’s the WCHA’s top scorer and has been one of the nation’s leading goal scorers all season, Frattin has elevated his play and “found another gear” heading into the playoffs, Sioux coach Dave Hakstol said.

“He’s such a fiery competitor,” said Hakstol, who’s in his seventh season at UND. “He’s highly competitive. He’s a big-time player and he’s responding that way.”

Frattin knows that not only is his last year at UND nearing an end, but he also understands the one-and-done finality of the NCAA tournament. The past two seasons, UND has been knocked out of the first round by Yale and New Hampshire in one-goal games.

“You think of it like your time is starting to run short,” he said. “So every game, every shift, you don’t want to leave anything out on the ice. You give it your all every game you’re in.”

The 6-foot, 206-pound native of Edmonton, Alberta, has demonstrated why he was drafted by the NHL’s Toronto Maple Leafs and is being touted as a candidate for the Hobey Baker Award. His 29 goals (tied for first nationally) and 20 assists have helped the Sioux to their best regular-season record (26-8-3, 21-6-1 WCHA) under Hakstol, despite playing one of the toughest schedules in the country.

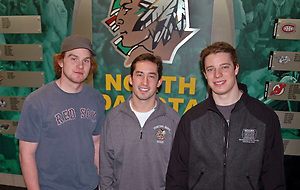

“Just as much as he’s a goal scorer, he plays Sioux hockey,” said Brad “Pony” Malone who centers an all-senior line dubbed the “Pony Express” with Frattin and Evan Trupp on the wings. “He kills penalties, he blocks shots and he throws some really big hits.

“Around here, being physical is part of our tradition and part of what we take pride in,” Malone continued. “I don’t think it matters if a guy is 6-foot or 6-8. Matt sees him as an opponent, and he’s going to try to run through him. He’s fearless, and that makes him the kind of player that he is.”

The power of Frattin’s shot, the fierceness of the hits he delivers and his strength on the puck can make him seem bigger on the ice than he appears in person.

“He’s got those tree-trunk legs that make him so explosive and so fast,” Trupp said. “He’s got a lot of muscle on that 6-foot frame.”

Kicked off the team

Less than two years ago, it seemed improbable that Frattin would still be playing at UND, let alone be considered for the award presented annually to college hockey’s best player.

Following two arrests in Grand Forks during the summer of 2009, Hakstol announced just before the fall semester that Frattin had been suspended indefinitely.

Trupp, who has been Frattin’s roommate for three years, said: “I remember when he called me and said he was getting kicked off the team. I thought he was joking at first, and then it kind of hit me.”

The punishment, however, was not unexpected.

“You kind of think something’s coming,” Frattin said. “You get arrested once and you get arrested again a month later. You know some discipline’s coming because you’ve been told you can’t get in trouble any more. The suspension was definitely a surprise, but something that needed to happen.”

Hakstol never closed the door on Frattin’s return to UND and laid out a process for him to follow if he wanted to rejoin the team. Frattin went back to Edmonton, lived with his parents, got a job, stayed in shape and turned his life around. And he remained in contact with two of his best friends on the team, Trupp and Malone.

“We encouraged him to come back,” Trupp said. “We definitely weren’t ready for him to leave.”

“When he was gone, it was like missing the third leg of the tripod,” Malone said. “Obviously, life went on, but we were wishing that he was with us.”

Although Frattin had an opportunity to sign a pro contract and leave his troubles in Grand Forks behind, that’s not what he wanted to do.

“The biggest thing was to face it straight on,” he said. “I didn’t want to leave here with the reputation that got me suspended.

“It wasn’t like I was burning bridges,” Frattin added. “I had really good friendships here. I just made two bad mistakes that cost me a suspension and a wake-up call, which I needed. Those friendships that I made the last four years in college are going to last a lifetime.”

Frattin pleaded guilty in August 2009 to a disorderly conduct charge for which he received a fine, a suspended sentence and one year of probation. In February 2010, a jury found him not guilty of driving under the influence.

“Everybody makes mistakes in their lives,” Frattin said. “It’s how you pick yourself up after them and learn from them.”

Hakstol has no doubt that Frattin learned the right lessons.

“When you factor in the decisions Matt made along the way, it tells you a little bit about his commitment and his conviction,” he said. “His care for how people overall thought of him and his reputation were important to him. There’s no question it was part of his motivation. He realized at the time that he was a little off track and needed to readjust the priorities in his life to pursue the opportunities that were in front of him.”

Making a comeback

When Hakstol allowed Frattin to rejoin the Sioux for the second half of last season, some characterized it as a desperation move to help a struggling team. But the UND coach explained that there was never any guarantee that Frattin could rejoin the team and that his decision had nothing to do with how the team was playing at the time.

“We went through a process that was clearly laid out,” Hakstol said. “I’m not worried about the public appearance of the process. I know we did everything the right way. Most importantly, I know that Matt did everything the right way. That’s what I cared about.”

Having Frattin back didn’t provide the Sioux with an instant boost. UND went 4-5-2 in the first 11 games he played. He had three assists and a minus-2 plus/minus rating.

All that changed during a February road series at SCSU when a line with Frattin, Malone and Trupp took to the ice. Frattin scored his first two goals of the season and the trio has been together for nearly every game since.

“If you think about it from a big-picture perspective, there’s a natural fit to the different abilities they have,” Hakstol said. “They are great friends, so the chemistry was quick and easy for them to build.”

At 6-2, 212 pounds, Malone is a strong, fast, hard-hitting center who’s never shy about mucking it up in front of the net. On the left wing, the 5-9, 174-pound Trupp is a creative playmaker with a scoring touch.

Frattin, a sniper with a power forward’s mentality, anchors the right wing. During the 13 games in which the three played together last season, UND went 11-2. Frattin had 11 goals, eight assists and was plus-10.

“We had tried Matt in a couple different areas,” Hakstol said. “He was working through not having played for four months. Maybe it was a bit of coincidence between him playing and the line combination coming together that seemed to ignite him and the other two guys.”

This season, the three members of the “Pony Express” line have played all but six games together and are having the best years of their college careers. Malone has 12 goals and 21 assists while Trupp has 16 goals and 18 assists.

“With the chemistry we’ve built, all it takes is one shift and it can change a game, which we’ve done a couple times this year,” Frattin said.

Hakstol agreed, noting that the line doesn’t necessarily have to score to alter the complexion of a game. Sometimes it’s a big hit that gets the bench fired up. Other times, it’s a hard-working shift that draws a penalty or inspires the team when it’s playing flat.

“You spend a good part of the season looking for those combinations that fit together,” he said. “This one, on paper, seems to add up, and it does because of the way the guys push themselves and the poise and the presence they have as seniors. It’s a real important factor for our team and for them when they are put in different situations in a game.”

Frattin says he has no regrets about his past because he’s grown from the experience, but if he could start over again, he’d do some things differently.

“I think the first couple of years I was taking school at North Dakota and the hockey team for granted,” he said. “I was kind of living my life just like a regular college student. I wasn’t really living my life like a Fighting Sioux hockey player. I’d probably limit some of the partying time and that kind of stuff.”

When Malone and Trupp were asked if their friend of the past four years has changed, Trupp smiled and replied, “He’s still Frats.”

Turning more serious, Trupp continued: “Maybe one thing is that he’s a little more professional at times. He’s one of the guys that everyone looks up to and he sets a good example for everyone. He works extremely hard. The younger guys can use that as a role model.”

Malone added: “He’s very professional around the rink, but in the locker room and the weight room, he’s probably one of the loudest and goofiest guys there is. He’s just a good teammate.”

Hakstol has coached long enough to know that each player goes through a different process of development. He’s confident that no matter how UND’s season ends, Frattin will be ready for the next level in hockey, both as a player and a person.

“There were a lot of tough things and unfair things said about him a year and a half ago,” he said. “You take the good out of it, and I think he’s really matured in all areas of his life.”

Comments are closed.